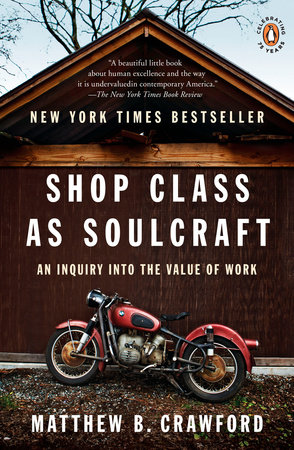

Shop Class as Soulcraft: An Inquiry into the Value of Work by Matthew B. Crawford

(New York: Penguin, 2009), 256

Introduction

- most surprisingly, I often find manual work more engaging intellectually. (Page: 5)

- It also explores what we might call the ethics of maintenance and repair, and in doing so I hope it will speak to those who may be unlikely to go into the trades professionally but strive for some measure of self-reliance—the kind that requires focused engagement with our material things. (Page: 6)

- What follows is an attempt to map the overlapping territories intimated by the phrases “meaningful work” and “self-reliance.” Both ideals are tied to a struggle for individual agency, which I find to be at the very center of modern life. (Page: 7)

1 A Brief Case for the Useful Arts

- “We have a generation of students that can answer questions on standardized tests, know factoids, but they can’t do anything,” (Page: 12)

- one of the fastest-growing segments of the student body at community colleges is people who already have a four-year degree and return to get a marketable trade skill. (Page: 12)

- The Psychic Satisfactions of Manual Work

- Craftsmanship has been said to consist simply in the desire to do something well, for its own sake. (Page: 14)

- The satisfactions of manifesting oneself concretely in the world through manual competence have been known to make a man quiet and easy. They seem to relieve him of the felt need to offer chattering interpretations of himself to vindicate his worth. He can simply point: the building stands, the car now runs, the lights are on. Boasting is what a boy does, because he has no real effect in the world. But the tradesman must reckon with the infallible judgment of reality, where one’s failures or shortcomings cannot be interpreted away. (Page: 15)

- Shared memories attach to the material souvenirs of our lives, and producing them is a kind of communion, with others and with the future. (Page: 15)

- as Hannah Arendt writes, the durable objects of use produced by men “give rise to the familiarity of the world, its customs and habits of intercourse between men and things as well as between men and men.” “The reality and reliability of the human world rest primarily on the fact that we are surrounded by things more permanent than the activity by which they were produced, and potentially even more permanent than the lives of their authors.” (Page: 16)

- The craftsman is proud of what he has made, and cherishes it, while the consumer discards things that are perfectly serviceable in his restless pursuit of the new.8 (Page: 17)

- The craftsman’s habitual deference is not toward the New, but toward the objective standards of his craft. (Page: 19)

- Craftsmanship entails learning to do one thing really well, while the ideal of the new economy is to be able to learn new things, celebrating potential rather than achievement. (Page: 19)

- The Cognitive Demands of Manual Work

- Skilled manual labor entails a systematic encounter with the material world, precisely the kind of encounter that gives rise to natural science. (Page: 21)

- Many inventions capture a reflective moment in which some worker has made explicit the assumptions that are implicit in his skill. (Page: 23)

- I quickly realized there was more thinking going on in the bike shop than in my previous job at the think tank. (Page: 27)

- Art, Crafts, and the Assembly Line

- Lears writes, “toward the end of the nineteenth century, many beneficiaries of modern culture began to feel they were its secret victims.” (Page: 28)

- As Lears tells the story, the great irony is that anti-modernist sentiments of aesthetic revolt against the machine paved the way for certain unattractive features of late-modern culture: therapeutic self-absorption and the hankering after “authenticity,” precisely those psychic hooks now relied upon by advertisers. (Page: 29)

- Such a partition of thinking from doing has bequeathed us the dichotomy of white collar versus blue collar, corresponding to mental versus manual. (Page: 31)

- My purpose in this book is to elaborate the potential for human flourishing in the manual trades—their rich cognitive challenges and psychic nourishment—rather (Page: 32)

- The Future of Work: Back to the Past?

- Blinder suggests the crucial distinction in the labor market will be between what he calls “personal services” and “impersonal services.” The former either require face-to-face contact or are inherently tied to a specific site. (Page: 33)

- “you can’t hammer a nail over the Internet.” (Page: 34)

- The MIT economist Frank Levy makes a complementary argument. He puts the issue not in terms of whether a service can be delivered electronically or not, but rather whether the service is itself rules-based or not. (Page: 34)

2 The Separation of Thinking from Doing

- wherever the separation of thinking from doing has been achieved, it has been responsible for the degradation of work. (Page: 37)

- the degradation of work is ultimately a cognitive matter, rooted in the separation of thinking from doing. (Page: 38)

- The Degradation of Blue-Collar Work

- The central culprit in Braverman’s account is “scientific management,” which “enters the workplace not as the representative of science, but as the representative of management masquerading in the trappings of science.” (Page: 38)

- Frederick Winslow Taylor, whose Principles of Scientific Management (Page: 38)

- gathering together all of the traditional knowledge which in the past has been possessed by the workmen and then of classifying, tabulating, and reducing this knowledge to rules, laws, and formulae.” (Page: 39)

- Thus craft knowledge dies out, or rather gets instantiated in a different form, as process engineering knowledge. (Page: 40)

- Contradicting the assumptions of “rational behavior,” it was found that when employers would increase the piece rate in order to boost production, it actually had the opposite effect: workers would produce less, as now they could meet their fixed needs with less work. Eventually it was learned that the only way to get them to work harder was to play upon the imagination, stimulating new needs and wants. (Page: 43)

- The habituation of workers to the assembly line was thus perhaps made easier by another innovation of the early twentieth century: consumer debt. As Jackson Lears has argued, through the installment plan previously unthinkable acquisitions became thinkable, and more than thinkable: it became normal to carry debt. (Page: 43)

- The Degradation of White-Collar Work

- Yet trafficking in abstractions is not the same as thinking. (Page: 44)

- the cognitive elements of the job are appropriated from professionals, instantiated in a system or process, and then handed back to a new class of workers—clerks—who replace the professionals. (Page: 44)

- It seems to be our liberal political instincts that push us in this direction of centralizing authority; we distrust authority in the hands of individuals. (Page: 45)

- genuine knowledge work comes to be concentrated in an ever-smaller elite. (Page: 47)

- Everyone an Einstein

- The truth, of course, is that creativity is a by-product of mastery of the sort that is cultivated through long practice. (Page: 51)

- The Tradesman as Stoic

- work is toilsome and necessarily serves someone else’s interests. That’s why you get paid. (Page: 52)

- The trades are then a natural home for anyone who would live by his own powers, free not only of deadening abstraction but also of the insidious hopes and rising insecurities that seem to be endemic in our current economic life. Freedom from hope and fear is the Stoic ideal. (Page: 53)

3 To Be Master of One’s Own Stuff

- This man would gladly hover around the mechanic’s bay and be educated about his car, but this is not allowed. (Page: 54)

- The idea of opportunity costs presumes the fungibility of human experience: all our activities are equivalent or interchangeable once they are reduced to the abstract currency of clock time, and its wage correlate. (Page: 55)

- Economics recognizes only certain virtues, and not the most impressive ones at that. (Page: 55)

- It’s true, some people fail to turn off a manual faucet. With its blanket presumption of irresponsibility, the infrared faucet doesn’t merely respond to this fact, it installs it, giving it the status of normalcy. There is a kind of infantilization at work, and it offends the spirited personality. (Page: 56)

- The Motorcycle as Mule

- On Lubrication: From the Hand Pump to the Idiot Light, and Beyond (Page: 58)

- Old bikes don’t flatter you, they educate you. (Page: 59)

- There are now layers of collectivized, absentee interest in your motor’s oil level, and no single person is responsible for it. (Page: 62)

- Agency versus Autonomy

- Thinking about manual engagement seems to require nothing less than that we consider what a human being is. (Page: 63)

- The musician’s power of expression is founded upon a prior obedience; her musical agency is built up from an ongoing submission. (Page: 64)

- I believe the example of the musician sheds light on the basic character of human agency, namely, that it arises only within concrete limits that are not of our making. (Page: 64)

- These limits need not be physical; the important thing is rather that they are external to the self. (Page: 64)

- The Betty Crocker Cruiser

- But choosing is not creating, however much “creativity” is invoked in such marketing. (Page: 68)

- Displaced Agency

- Paradoxically, we are narcissistic but not proud enough. (Page: 71)

4 The Education of a Gearhead

- the work a man does forms him. (Page: 73)

- The Would-be Apprentice

- String Theory

- Yet the kind of thinking that begins from idealizations such as the frictionless surface and the perfect vacuum sometimes fails us (as my dad’s advice failed me), because it isn’t sufficiently involved with the particulars. (Page: 80)

- The mechanic and the doctor deal with failure every day, even if they are expert, whereas the builder does not. This is because the things they fix are not of their own making, and are therefore never known in a comprehensive or absolute way. (Page: 81)

- I believe the mechanical arts have a special significance for our time because they cultivate not creativity, but the less glamorous virtue of attentiveness. Things need fixing and tending no less than creating. (Page: 82)

- The Mentor

- Forensic Wrenching

- Personal Knowledge

- We usually think of intellectual virtue and moral virtue as being very distinct things, but I think they are not. (Page: 95)

- This is the Truth, and it is the same for everyone. But finding this truth requires a certain disposition in the individual: attentiveness, enlivened by a sense of responsibility (Page: 98)

- The truth does not reveal itself to idle spectators. (Page: 98)

- Seeing Clearly, or Unselfishly

- Idiocy as an Ideal

- There seems to be a vicious circle in which degraded work plays a pedagogical role, forming workers into material that is ill suited for anything but the overdetermined world of careless labor. (Page: 101)

5 The Further Education of a Gearhead: From Amateur to Professional

- To respond to the world justly, you have to see it clearly, and for this you have to get outside your own head. Knowing you’re going to have to explain your labor bill to a customer accomplishes just this. (Page: 103)

- Stepping outside the intellectually serious circle of my teachers and friends at Chicago into the broader academic world, it struck me as an industry hostile to thinking. (Page: 104)

- The Motorcycle Antiquarian

- This wasn’t work befitting a free man, and the tie I wore started to feel like the mark of the slave. (Page: 109)

- Shockoe Moto

- Writing Service Tickets

- Of Madness, a Magna, and Metaphysics

- I was nearing a familiar point where I’ve descended through every level of madness and despair, and a certain calm takes over. I was reduced now to a more or less autistic repetition of valve cover manipulations I’d long ago determined to be futile, when suddenly the cover just fell out of its trap and lay free in my hand. (Page: 119)

- In digging at that oil seal heedlessly, I was acting out of some need of my own. The curious man is always a fornicator, according to Saint Augustine. (Page: 123)

- But agreement and convention, if consulted, provide a helpful check on your own subjectivity—they offer proof that you are not insane, or at least a more robust presumption to that effect. Some of us need such proof more than others, and getting paid for what you love to do can provide it. Going into business is good therapy for the feeling that there is something arbitrary and idiosyncratic in your grasp of the world, and therefore that your actions within it are unjustified. (Page: 124)

- being a clear-sighted person who looks around and sees the whole situation, isn’t something I can take for granted in myself. It is something that needs to be achieved on a moment-to-moment basis. The presence of others in a shared world makes this both possible and necessary. (Page: 125)

6 The Contradictions of the Cubicle

- He is not so much a boss as a life coach. (Page: 128)

- The contemporary office requires the development of a self that is ready for teamwork, rooted in shared habits of flexibility rather than strong individual character. (Page: 128)

- At issue in the contrast between office work and the manual trades is the idea of individual responsibility, tied to the presence or absence of objective standards. (Page: 128)

- Indexing and Abstracting

- So the job required both dumbing down and a bit of moral reeducation. (Page: 134)

- I was not held to an external, objective standard. (Page: 135)

- Learned Irresponsibility

- Managers are placed in the middle of an enduring social conflict that once gave rise to street riots but is mostly silent in our times: the antagonism between labor and capital. (Page: 138)

- I believe some of the contradictions of “knowledge work” such as I experienced at Information Access Company can be traced to an imperative of abstraction, and that this imperative in turn may be understood as a device that upper-level managers use, quite understandably, to cope with the psychic demands of their own jobs. (Page: 138)

- managers have to spend a good part of the day “managing what other people think of them.” (Page: 138)

- A good part of the job, then, consists of “a constant interpretation and reinterpretation of events that constructs a reality in which it is difficult to pin blame on anyone, especially oneself,” according to Calhoun. This gives rise to the art of talking in circles. (Page: 139)

- the corporation is a place where people are not held to what they say because it is generally understood that their word is always provisional.” (Page: 139)

- When a manager’s success is predicated on the manipulation of language, for the sake of avoiding responsibility, reward and blame come untethered from good faith effort. (Page: 140)

- Interlude: What College Is For

- Is this our society as a whole, buying more education only to scale new heights of stupidity? (Page: 144)

- more powerful minds, but in this perverse sense: college habituates young people to accept as the normal course of things a mismatch between form and content, official representations and reality. (Page: 147)

- Teamwork

- The rise of teamwork coincides with the discovery of “corporate culture” by management theorists in the late 1970s. (Page: 148)

- The division between private life and work life is eroded, and accordingly the whole person is at issue in job performance evaluations. (Page: 149)

- The Crew versus the Team

- Alexis de Tocqueville foresaw a “soft despotism” in which Americans would increasingly seek their security in, and become dependent upon, the state. (Page: 155)

- the softly despotic tendencies of a nanny state are found in the large commercial enterprise as well, (Page: 155)

- Tocqueville also saw a remedy for this evil, however: the small commercial enterprise, (Page: 155)

- Not surprisingly, it is the office rather than the job site that has seen the advent of speech codes, diversity workshops, and other forms of higher regulation. (Page: 157)

- reason is that when there is no concrete task that rules the job—an autonomous good that is visible to all—then there is no secure basis for social relations. Maintaining consensus and preempting conflict become the focus of management, (Page: 157)

7 Thinking as Doing

- The current educational regime is based on a certain view about what kind of knowledge is important: “knowing that,” as opposed to “knowing how.” (Page: 161)

- If thinking is bound up with action, then the task of getting an adequate grasp on the world, intellectually, depends on our doing stuff in it. (Page: 164)

- Of Ohm’s Law and Muddy Boots

- Appreciating the situated character of the kind of thinking we do at work is important, because the degradation of work is often based on efforts to replace the intuitive judgments of practitioners with rule following, and codify knowledge into abstract systems of symbols that then stand in for situated knowledge. (Page: 166)

- The Tacit Knowledge of the Firefighter and the Chess Master

- tacit knowledge is that we know more than we can say, and certainly more than we can specify in a formulaic way. (Page: 168)

- The fact that a firefighter’s knowledge is tacit rather than explicit, and therefore not capable of articulation, means that he is not able to give an account of himself to the larger society. He is not able to make a claim for the value of his mind in the terms that prevail, and may come to doubt it himself. But his own experience provides grounds for a radical critique of the view that theoretical knowledge is the only true knowledge. (Page: 171)

- Personal Knowledge versus Intellectual Technology

- The Service Manual as Social Technology

8 Work, Leisure, and Full Engagement

- The Groove of the Speed Shop

- Community

- Can the speed shop teach us anything about the tension between work and leisure, and how it might be eased in the direction of a coherent life? (Page: 185)

- Here work and leisure both take their bearings from something basically human: rational activity, in association with others. (Page: 185)

- When the maker’s (or fixer’s) activity is immediately situated within a community of use, it can be enlivened by this kind of direct perception. Then the social character of his work isn’t separate from its internal or “engineering” standards; the work is improved through relationships with others. (Page: 187)

- Wholehearted Activity

- To be capable of sustaining our interest, a job has to have room for progress in excellence. (Page: 195)

- if we follow the traces of our own actions to their source, they intimate some understanding of the good life. (Page: 197)

- Concluding Remarks on Solidarity and Self-Reliance

- any job that can be scaled up, depersonalized, and made to answer to forces remote from the scene of work is vulnerable to degradation, (Page: 198)

- The special appeal of the trades lies in the fact that they resist this tendency toward remote control, because they are inherently situated in a particular context. (Page: 199)

- In the best cases, the building and fixing that they do are embedded in a community of using. Face-to-face interactions are still the norm, you are responsible for your own work, and clear standards provide the basis for the solidarity of the crew, as opposed to the manipulative social relations of the office “team.” (Page: 199)

- I have argued that real knowledge arises through confrontations with real things. (Page: 199)

- in the best cases, work may itself approach the good sought in philosophy, understood as a way of life: a community of those who desire to know. (Page: 199)

- Solidarity and the Aristocratic Ethos

- The Importance of Failure

- Being unacquainted with failure, the kind that can’t be interpreted away, may have something to do with the lack of caution that business and political leaders often display in the actions they undertake on behalf of other people. (Page: 203)

- There may be something to be said, then, for having gifted students learn a trade, if only in the summers, so that their egos will be repeatedly crushed before they go on to run the country. (Page: 204)

- Individual Agency in a Shared World

- Too often, the defenders of free markets forget that what we really want is free men. (Page: 209)

- A heady vision of the progressive hereafter in which economic antagonism has been overcome may come to stand in for, and distract him from, the smaller but harder work of living well in this life. (Page: 210)

- The alternative to revolution, which I want to call Stoic, is resolutely this-worldly. It insists on the permanent, local viability of what is best in human beings. In practice, this means seeking out the cracks where individual agency and the love of knowledge can be realized today, in one’s own life. (Page: 210)

Created: 2018-09-01

Updated: 2022-12-04-Sun