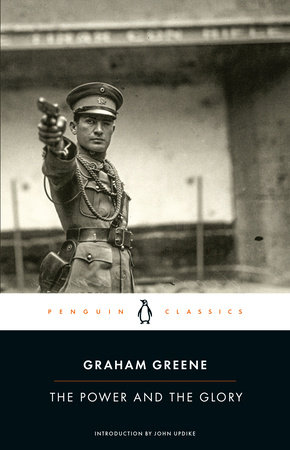

The Power and the Glory by Graham Greene

(London: Heinemann, 1940), 216

He was a bad priest, he knew it. They had a word for his kind—a whisky priest.

PART ONE

Chapter 1: THE PORT

- Mr Tench’s father had been a dentist too3)

- There is always one moment in childhood when the door opens and lets the future in. The hot wet river-port and the vultures lay in the wastepaper basket, and he picked them out. We should be thankful we cannot see the horrors and degradations lying around our childhood, in cupboards and bookshelves, everywhere. (3)

- ‘Let me see. What was it we were talking about? The kids … oh yes, the kids. It’s funny what a man remembers. You know, I can remember that watering-can better than I can remember the kids. It cost three and elevenpence three farthings, green; I could lead you to the shop where I bought it. But as for the kids,’ he brooded over his glass into the past, ‘I can’t remember much else but them crying.’ (4)

- ‘How happy it was then.’ ‘Was it? I didn’t notice.’ ‘They had at any rate—God.’ (4)

- ‘You know nothing,’ the stranger said fiercely. ‘That is what everyone says all the time—you do no good.’ The brandy had affected him. He said with monstrous bitterness, ‘I can hear them saying it all over the world.’ (5)

- He had the kind of dwarfed dignity Mr Tench was accustomed to—the dignity of people afraid of a little pain and yet sitting down with some firmness in his chair. Perhaps he didn’t care for mule travel. He said with an effect of old-fashioned ways, ‘I will pray for you.’ (5)

- He felt an unwilling hatred of the child ahead of him and the sick woman—he was unworthy of what he carried. (6)

- He began to pray, bouncing up and down to the lurching slithering mule’s stride, with his brandied tongue: ‘Let me be caught soon. … Let me be caught.’ He had tried to escape, but he was like the King of a West African tribe, the slave of his people, (6)

Chapter 2: THE CAPITAL

- One man had conformed to the Governor’s law that all priests must marry. He lived now near the river with his housekeeper. That, of course, was the best solution of all, to leave the living witness to the weakness of their faith. It showed the deception they had practised all these years. For if they really believed in heaven or hell, they wouldn’t mind a little pain now, in return for what immensities … The lieutenant, lying on his hard bed, in the damp hot dark, felt no sympathy at all with the weakness of the flesh. (8)

- As for the Church—the Church is Padre José and the whisky priest—I don’t know of any other. If we don’t like the Church, well, we must leave it.’ (9)

- She said, ‘I would rather die.’ ‘Oh,’ he said, ‘of course. That goes without saying. But we have to go on living.’ (9)

- He thought with envy of the men who had died: it was over so soon. They were taken up there to the cemetery and shot against the wall: in two minutes life was extinct. And they called that martyrdom. Here life went on and on; he was only sixty-two. He might live to ninety. (10)

Chapter 3: THE RIVER

- Fellows opened a tin box and ate a sandwich—food never tasted so good as out of doors. (11)

- He hadn’t any right …’ ‘Oh, right,’ Captain Fellows said. ‘They carry their right on their hips. (13)

- He remembered with self-pity and nostalgia his happiness on the river, doing a man’s job without thinking of other people. If I had never married. … (13)

- ‘You see how unworthy I am. Talking like this.’ (14)

- She said, ‘Of course you could—renounce.’ ‘I don’t understand.’ ‘Renounce your faith,’ she explained, using the words of her European History. He said, ‘It’s impossible. There’s no way. I’m a priest. It’s out of my power.’ (14)

- He said, ‘You are very good. Will you pray for me?’ ‘Oh,’ she said, ‘I don’t believe in that.’ ‘Not in praying?’ ‘You see, I don’t believe in God. I lost my faith when I was ten.’ ‘Well, well,’ he said. ‘Then I will pray for you.’ (15)

- ‘A little drink,’ he said, ‘will work wonders in a cowardly man. With a little brandy, why, I’d defy—the devil.’ (15)

- They were not hard-hearted; they were watching the rare spectacle of something worse off than themselves. (15)

- ‘Were you expecting me?’ ‘No, father. But it is five years since we have seen a priest … (16)

- ‘Oh, let them come. Let them all come,’ the priest cried angrily. ‘I am your servant.’ He put his hand over his eyes and began to weep. (16)

Chapter 4: THE BYSTANDERS

- He sank hopelessly down on his knees and entreated them: ‘Leave me alone.’ He said, ‘I am unworthy. Can’t you see?—I am a coward.’ (18)

- He knew he was in the grip of the unforgivable sin, despair. (18)

- ‘One day they’ll forget there ever was a Church here.’ (21)

- It was for these he was fighting. He would eliminate from their childhood everything which had made him miserable, all that was poor, superstitious, and corrupt. They deserved nothing less than the truth—a vacant universe and a cooling world, the right to be happy in any way they chose. (22)

PART TWO

Chapter 1

- It is one of the strange discoveries a man can make that life, however you lead it, contains moments of exhilaration; there are always comparisons which can be made with worse times: even in danger and misery the pendulum swings. (22)

- The cause of his happiness came back to him like the taste of brandy, promising temporary relief from fear, loneliness, a lot of things. He was being driven by the presence of soldiers to the very place where he most wanted to be. He had avoided it for six years, but now it wasn’t his fault—it was his duty to go there—it couldn’t count as sin. He went back to his mule and kicked it gently, ‘Up, mule, up,’ a small gaunt man in torn peasant’s clothes going for the first time in many years, like any ordinary man, to his home. In any case, even if he could have gone south and avoided the village, it was only one more surrender. The years behind him were littered with similar surrenders—feast days and fast days and days of abstinence had been the first to go: then he had ceased to trouble more than occasionally about his breviary—and finally he had left it behind altogether at the port in one of his periodic attempts at escape. Then the altar stone went—too dangerous to carry with him. He had no business to say Mass without it; he was probably liable to suspension, but penalties of the ecclesiastical kind began to seem unreal in a state where the only penalty was the civil one of death. The routine of his life like a dam was cracked and forgetfulness came dribbling through, wiping out this and that. Five years ago he had given way to despair—the unforgivable sin—and he was going back now to the scene of his despair with a curious lightening of the heart. For he had got over despair too. He was a bad priest, he knew it. They had a word for his kind—a whisky priest, but every failure dropped out of sight and mind: somewhere they accumulated in secret—the rubble of his failures. One day they would choke up, he supposed, altogether the source of grace. Until then he carried on, with spells of fear, weariness, with a shamefaced lightness of heart. (22)

- Now that he no longer despaired it didn’t mean, of course, that he wasn’t damned—it was simply that after a time the mystery became too great, a damned man putting God into the mouths of men: an odd sort of servant, that, for the devil. His mind was full of a simplified mythology: Michael dressed in armour slew a dragon, and the angels fell through space like comets with beautiful streaming hair because they were jealous, so one of the Fathers had said, of what God intended for men—the enormous privilege of life—this life. (23)

- It was as if he had descended by means of his sin into the human struggle to learn other things besides despair and love, that a man can be unwelcome even in his own home. (23)

- He thought: if I go, I shall meet other priests: I shall go to confession: I shall feel contrition and be forgiven: eternal life will begin for me all over again. The Church taught that it was every man’s first duty to save his own soul. The simple ideas of hell and heaven moved in his brain; life without books, without contact with educated men, had peeled away from his memory everything but the simplest outline of the mystery. (24)

- If he left them, they would be safe, and they would be free from his example. He was the only priest the children could remember: it was from him they would take their ideas of the faith. But it was from him too they took God—in their mouths. When he was gone it would be as if God in all this space between the sea and the mountains ceased to exist. Wasn’t it his duty to stay, even if they despised him, even if they were murdered for his sake? even if they were corrupted by his example? He was shaken with the enormity of the problem. (24)

- He was aware of an immense load of responsibility: it was indistinguishable from love. (25)

- He caught the look in the child’s eyes which frightened him—it was again as if a grown woman was there before her time, making her plans, aware of far too much. It was like seeing his own mortal sin look back at him, without contrition. (25)

- He thought of his own death and her life going on; it might be his hell to watch her rejoining him gradually through the debasing years, sharing his weakness like tuberculosis. (26)

- ‘This is a part of heaven just as pain is a part of pleasure.’ He said, ‘Pray that you will suffer more and more and more. Never get tired of suffering. The police watching you, the soldiers gathering taxes, the beating you always get from the jefe because you are too poor to pay, smallpox and fever, hunger … that is all part of heaven—the preparation. Perhaps without them, who can tell, you wouldn’t enjoy heaven so much. (26)

- There was a time when he had approached the Canon of the Mass with actual physical dread—the first time he had consumed the body and blood of God in a state of mortal sin. But then life bred its excuses. (27)

- In the inadequate light he could just see two men kneeling with their arms stretched out in the shape of a cross—they would keep that position until the consecration was over, one more mortification squeezed out of their harsh and painful lives. He felt humbled by the pain ordinary men bore voluntarily; (27)

- Heaven must contain just such scared and dutiful and hunger-lined faces. For a matter of seconds he felt an immense satisfaction that he could talk of suffering to them now without hypocrisy. (27)

- Maria cried, ‘Why, the child doesn’t know her own name. Ask her who her father is.’ ‘Who’s your father?’ The child stared up at the lieutenant and then turned her knowing eyes upon the priest … ‘Sorry and beg pardon for all my sins,’ he was repeating to himself with his fingers crossed for luck. The child said, ‘That’s him. There.’ ‘All right,’ the lieutenant said, ‘Next.’ (29)

- Death was not the end of pain—to believe in peace was a kind of heresy. (29)

- He said, ‘Lieutenant …’ ‘What do you want?’ ‘I’m getting too old to be much good in the fields. Take me.’ (30)

- The priest said aloud, ‘I did my best.’ He went on, ‘It’s your job—to give me up. What do you expect me to do? It’s my job not to be caught.’ (30)

- You’re no good any more to anyone,’ she said fiercely. ‘Don’t you understand, father? We don’t want you any more.’ ‘Oh yes,’ he said. ‘I understand. But it’s not what you want—or I want …’ (30)

- He felt envious of the unknown gringo whom they wouldn’t hesitate to trap—he at any rate had no burden of gratitude to carry round with him. (31)

- He prayed silently, ‘O God, give me any kind of death—without contrition, in a state of sin—only save this child.’ (31)

- He said, ‘I would give my life, that’s nothing, my soul … my dear, my dear, try to understand that you are—so important.’ That was the difference, he had always known, between his faith and theirs, the political leaders of the people who cared only for things like the state, the republic: this child was more important than a whole continent. He said, ‘You must take care of yourself because you are so—necessary. The president up in the capital goes guarded by men with guns—but my child, you have all the angels of heaven.’ (32)

- ‘You talk like a priest.’ He came quickly awake, but under the tall dark trees he could see nothing. He said, ‘What nonsense you talk.’ ‘I am a very good Christian,’ the man said, stroking the priest’s foot. ‘I dare say. I wish I were.’ (34)

- A man must retain some sentimental relics if he is to live at all. (35)

- What hour did the cocks crow? One of the oddest things about the world these days was that there were no clocks—you could go a year without hearing one strike. They went with the churches, and you were left with the grey slow dawns and the precipitate nights as the only measurements of time. (39)

- But at the centre of his own faith there always stood the convincing mystery—that we were made in God’s image. God was the parent, but He was also the policeman, the criminal, the priest, the maniac, and the judge. Something resembling God dangled from the gibbet or went into odd attitudes before the bullets in a prison yard or contorted itself like a camel in the attitude of sex. He would sit in the confessional and hear the complicated dirty ingenuities which God’s image had thought out, and God’s image shook now, up and down on the mule’s back, with the yellow teeth sticking out over the lower lip, and God’s image did its despairing act of rebellion with Maria in the hut among the rats. He said, ‘Do you feel better now? Not so cold, eh? Or so hot?’ and pressed his hand with a kind of driven tenderness upon the shoulders of God’s image. (39)

Chapter 2

- ‘Why, man, you’re crying.’ All three watched the man in drill with their mouths a little open. He said, ‘It always takes me like this—brandy. Forgive me, gentlemen. I get drunk very easily and then I see …’ ‘See what?’ ‘Oh, I don’t know, all the hope of the world draining away.’ (44)

- He knew it was the beginning of the end—after all these years. He began to say silently an act of contrition, while they picked the brandy bottle out of his pocket, but he couldn’t give his mind to it. That was the fallacy of the death-bed repentance—penitence was the fruit of long training and discipline: fear wasn’t enough. (47)

Chapter 3

- It was like the end: there was no need to hope any longer. The ten years’ hunt was over at last. There was silence all round him. This place was very like the world: overcrowded with lust and crime and unhappy love, it stank to heaven; but he realized that after all it was possible to find peace there, when you knew for certain that the time was short. (49)

- He said, ‘My child, the thief repented. I haven’t repented.’ He remembered her coming into the hut, the dark malicious knowing look with the sunlight at her back. He said, ‘I don’t know how to repent.’ That was true: he had lost the faculty. He couldn’t say to himself that he wished his sin had never existed, because the sin seemed to him now so unimportant and he loved the fruit of it. He needed a confessor to draw his mind slowly down the drab passages which led to grief and repentance. (50)

- He was just one criminal among a herd of criminals … He had a sense of companionship which he had never experienced in the old days when pious people came kissing his black cotton glove. (51)

- The pious woman said aloud with fury, ‘Why won’t they stop it? The brutes, the animals!’ ‘What’s the good of your saying an Act of Contrition now in this state of mind?’ ‘But the ugliness …’ ‘Don’t believe that. It’s dangerous. Because suddenly we discover that our sins have so much beauty.’ (52)

- That was another mystery: it sometimes seemed to him that venial sins—impatience, an unimportant lie, pride, a neglected opportunity—cut you off from grace more completely than the worst sins of all. Then, in his innocence, he had felt no love for anyone; now in his corruption he had learnt… (55)

Chapter 4

- Hope is an instinct only the reasoning human mind can kill. An animal never knows despair. (56)

- All around was the gentle noise of the dripping water. It was nearly like peace, but not quite. For peace you needed human company—his aloneness was like a threat of things to come. (59)

- Why should anyone listen to his prayers? Sin was a constriction which prevented their escape; he could feel his prayers weigh him down like undigested food. (61)

PART THREE

Chapter 1

- The priest got up again and drank more water. He wasn’t very thirsty; he was satisfying a sense of luxury. (64)

- God might forgive cowardice and passion, but was it possible to forgive the habit of piety? He remembered the woman in the prison and how impossible it had been to shake her complacency. It seemed to him that he was another of the same kind. He drank the brandy down like damnation: men like the half-caste could be saved, salvation could strike like lightning at the evil heart, but the habit of piety excluded everything but the evening prayer and the Guild meeting and the feel of humble lips on your gloved hand. (67)

- Loving God isn’t any different from loving a man—or a child. It’s wanting to be with Him, to be near Him.’ He made a hopeless gesture with his hands. ‘It’s wanting to protect Him from yourself.’ (69)

- In three days, he told himself, I shall be in Las Casas: I shall have confessed and been absolved, and the thought of the child on the rubbish-heap came automatically back to him with painful love. What was the good of confession when you loved the result of your crime? (70)

Chapter 2

- He prayed: ‘O merciful God, after all he was thinking of me, it was for my sake …’ but he prayed without conviction. At the best, it was only one criminal trying to aid the escape of another—whichever way you looked, there wasn’t much merit in either of them. (76)

Chapter 3

- ‘Oh well, lieutenant, you know how it is. Even a coward has a sense of duty.’ (76)

- ‘That’s another difference between us. It’s no good your working for your end unless you’re a good man yourself. And there won’t always be good men in your party. Then you’ll have all the old starvation, beating, get-rich-anyhow. But it doesn’t matter so much my being a coward—and all the rest. I can put God into a man’s mouth just the same—and I can give him God’s pardon. It wouldn’t make any difference to that if every priest in the Church was like me.’ (78)

- The fact is, a man isn’t presented suddenly with two courses to follow: one good and one bad. He gets caught up. (78)

- ‘Pride was what made the angels fall. Pride’s the worst thing of all. I thought I was a fine fellow to have stayed when the others had gone. And then I thought I was so grand I could make my own rules. I gave up fasting, daily Mass. I neglected my prayers—and one day because I was drunk and lonely—well, you know how it was, I got a child. It was all pride. (78)

- ‘Oh well, perhaps when you’re my age you’ll know the heart’s an untrustworthy beast. The mind is too, but it doesn’t talk about love. (80)

- ‘Listen,’ the priest said earnestly, leaning forward in the dark, pressing on a cramped foot, ‘I’m not as dishonest as you think I am. Why do you think I tell people out of the pulpit that they’re in danger of damnation if death catches them unawares? I’m not telling them fairy stories I don’t believe myself. I don’t know a thing about the mercy of God: I don’t know how awful the human heart looks to Him. But I do know this—that if there’s ever been a single man in this state damned, then I’ll be damned too.’ He said slowly, ‘I wouldn’t want it to be any different. I just want justice, that’s all.’ (80)

Chapter 4

- One didn’t trust one’s superiors when one was more successful than they were. He knew the jefe wasn’t pleased that he had brought the priest in—an escape would have been better from his point of view. (81)

- He said, ‘Oh God, help her. Damn me, I deserve it, but let her live for ever.’ This was the love he should have felt for every soul in the world: all the fear and the wish to save concentrated unjustly on the one child. (83)

- perhaps after all he was not at the moment afraid of damnation—even the fear of pain was in the background. He felt only an immense disappointment because he had to go to God empty-handed, with nothing done at all. It seemed to him, at that moment, that it would have been quite easy to have been a saint. It would only have needed a little self-restraint and a little courage. He felt like someone who has missed happiness by seconds at an appointed place. He knew now that at the end there was only one thing that counted—to be a saint. (84)

PART FOUR

- This was the last chapter, and in the last chapter things always happened violently. Perhaps all life was like that—dull and then a heroic flurry at the end. (87)

- ‘No need to have fired another shot. The soul of the young hero had already left its earthly mansion, and the happy smile on the dead face told even those ignorant men where they would find Juan now. One of the men there that day was so moved by his bearing that he secretly soaked his handkerchief in the martyr’s blood, and that handkerchief, cut into a hundred relics, found its way into many pious homes. (87)

- There were no more priests and no more heroes. (88)

2025-02-22-Sat Discussion

- he's not good, but he believes: She said, ‘Of course you could—renounce.’ ‘I don’t understand.’ ‘Renounce your faith,’ she explained, using the words of her European History. He said, ‘It’s impossible. There’s no way. I’m a priest. It’s out of my power.’ (14)

- themes

- home

- priest being nameless

- Mr. Tench can't get out because of a monetary crisis

- across the border as metaphor for heaven

- fear

- abandonment vs surrender

- duty

- betrayal and pride

- Becca: after he died all the secondary characters reappear and indicate how he changed them

- Similarities between the Lieutenant and the Whiskey Priest

Topic: Novel

Source

Created: 2023-09-03-Sun

Updated: 2025-03-19-Wed