After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory by Alasdair MacIntyre

(Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1981/1982 [2nd Edition]), 278

I first read After Virtue in a Morality & Modernity course taught by David Solomon at Notre Dame in the spring of 2011 to fulfill my second philosophy requirement. I enjoyed and [undeservedly] did well in the course without my mind in any way ready to really absorb MacIntyre's thought. I'm embarrassed to admit that after the course I sold the texts we read—including After Virtue—thinking I was done with them. I only bought a replacement copy a couple of years ago after other authors helped me see the full importance of what was wasted on me in my youth. Or perhaps not wasted, but simply a seed planted that has taken some time to germinate. I dug back in after reading Archbishop Chaput and am grateful for this reintroduction.

It's important to note that After Virtue is a first statement of the problem and a sketch of a possible solution but not the complete argument. MacIntyre says as much in the postscript to the Second Edition and prologue to the Third Edition, and the argument is further developed in his subsequent books which I plan to dive into eventually.

After Virtue starts by observing the problem that modern moral arguments are irreconcilable in nature and shrill in tone. MacIntyre argues that this is the result of the failure of the enlightenment project of justifying morality by removing man's teleological end. This leaves us with an emotivist approach to questions of morality where the answer is all a matter of preference. People and traditions clearly have different preferences, so this leaves us deadlocked. MacIntyre argues that the path forward is a rearticulation of the classical Aristotelian and Thomistic Virtues that recognize the unity of human life and a sense of history and culture. He concludes with a haunting comparison between our society and the Roman society at the Dark Ages and suggests that our hope rests in the emergence of a "new St. Benedict" and the formation of local communities where the virtues can be practiced in spite of the barbarians who now rule us.

Notes

Preface

- moral philosophy isn't an "independent and isolable" area of enquiry (ix)

Ch 1 - A Disquieting Suggestion

Summary: MacIntyre opens by suggesting that morality is in a state of disorder, having been vibrant before collapsing and then being restored in a distorted way. This begs the question: what to do?

- MacIntyre opens with an allusion to the world of A Canticle For Liebowitz: fragmented, misunderstanding, and subjectivist, and suggests that this is precisely the state of morality today (1-2)

- Morality flourished, then suffered catastrophe, then were restored but in a disordered way (3)

Ch 2 - The Nature of Moral Disagreement Today

Summary: MacIntyre observes that modern moral arguments are interminable and identifies the primary reason for this an Emotivist doctrine that holds all moral judgments to be merely expressions of personal preference.

- moral utterance today expresses disagreements that are characteristically interminable (6); examples include: war, abortion, education & healthcare (6-7)

- common characteristics of these debates include (8+):

- the arguments are logically valid but there is no way to rationally reconcile the premises

- they are impersonal

- they come from a variety of historical origins, often out of context and divorced from their original meaning (10)

- we are missing a historical narrative and hampered by the division of academic disciplines where moral philosophy is siloed (cf. James Turner's Philology) (11)

- Emotivism: "the doctrine that all evaluative judgments and more specifically all moral judgments are nothing but expressions of preference, expressions of attitude or feeling, insofar as they are moral or evaluative in character." (11-12) ^570a80

- The dominant modern theory to confront is emotivisim

- Emotivism says that moral judgments cannot be resolved rationally

- But emotivism fails: (12+):

- the subjective feelings/attitudes it is based on creates a circular reference

- emotivism incorrectly removes the separation between expressions of personal preference and evaluative (including moral) expressions

- emotivism obscures the distinction between [objective] meaning and [particular] use

- An emotivist is either the pinnacle of pretention, or unaware of exactly what they are doing:

- "people take themselves to be identifying the presence of a non-natural property...but there is in fact no such property and they are doing no more and no other than expressing their feelings and attitudes, disguising the expression of preference and whim by an interpretation of their own utterance and behavior which confers upon it an objectivity that id does not in fact possess." (17)

- "Emotivism thus rests upon a claim that every attempt to provide a rational justification for an objective morality has in fact failed. It is a verdict upon the whole history of moral philosophy." (19)

- "insofar as emotivism is justifiably believed, presumably the use of traditional and inherited moral language ought to be abandoned" (20)

Ch 3 - Emotivism: Social Content and Social Context

Summary: MacIntyre says a philosophy can't be understood apart from its social embodiment, and gives this view for emotivism through the lens of the emotivist characters.

- the claims of a moral philosophy can't be understood apart from its social embodiment, so MacIntyre does this for emotivism (23)

- he focuses on the Characters as moral representatives of their culture (28), which include (30):

- The Rich Aesthete: the consumer

- The Manager: manipulative social relations, transforms materials/investment into products/profit, treats the end as given and outside his scope

- The Therapist: transforms people, also treats the end as given and outside his scope

- emotivism is only clear as the end product of historical change (35)

Ch 4 - The Predecessor Culture and the Enlightenment Project of Justifying Morality

Summary: We have to understand the history of philosophy to understand how we got here

- we have to understand the history of philosophy to understand how we got here (36)

- discussion of Kierkegaard's Enten-Eller (39+)

- Kant's moral philosophy (43-44)

- if moral rules are rational, they are the same for all rational beings

- will to carry out these rules (not ability) is what matters

- a conception of our happiness is not sufficient to ground morality

Ch 5 - Why the Enlightenment Project of Justifying Morality Had to Fail

Summary: The secular removal of man's telos formed the incoherent inheritance that guaranteed the failure of the Enlightenment project.

- Enlightenment thinkers (Kierkegaard, Kant, Diderot, Hume, Smith, etc.) were inheritors of a specific scheme of moral beliefs whose internal incoherence ensured their failure before they started (51)

- Ancient scheme, the teleological scheme of Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics (52), which is furthered in the framework of theism by Thomas (53)

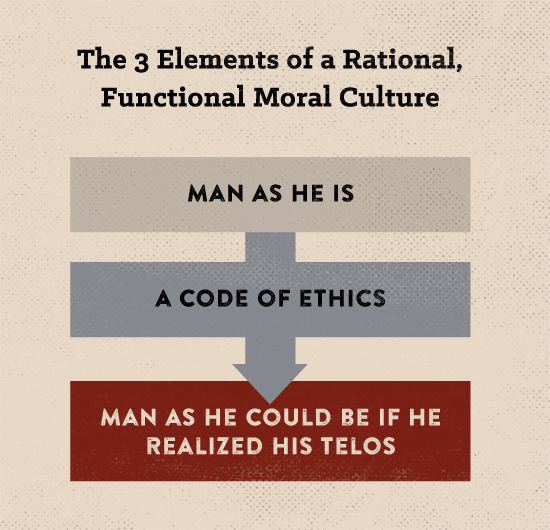

- The 3 Elements of a Rational, Functional Moral Culture (cf AOM):

- Man-as-he-happens-to-be

- An ethical code that allows a man to move from state #1 to state #3

- A view of man-as-he-could-be-if-he-realized-his-telos

- secularism eliminated the telos (54) and thus the Enlightenment inherited incoherent fragments of a once coherent whole (55)

Ch 6 - Some Consequences of the Failure of the Enlightenment Project

Summary: "Utility", "rights", and "expertise of the bureaucratic manager" are all moral fictions developed in the 17th & 18th centuries which contribute to the current incoherence.

- Utilitarianism serves as the new teleology to replace the removed teleology (62)

- discussion of the failure of utilitarianism as the "greatest happiness for the greatest number" due to the "polymorphous character of pleasure and happiness" (64)

- discussion of the new concept of "rights" (and difficulty justifying them) on 69-70

- MacIntyre rebuts managerial and bureaucratic "expertise" (in a way Taleb would appreciate) by observing that "the kind of knowledge which would be required to sustain it does not exist" (75)

- Two claims to justify a manager's authority (77):

- the existence of a domain of morally neutral "fact" about which the manager is to be the expert --> Taleb's "skin in the game"

- law-like generalizations and their applications to particular cases derived from the study of this domain --> Taleb's Platonicity

Ch 7 - 'Fact', Explanation and Expertise

Summary: MacIntyre explores the incompatibility between empiricism and natural science and suggests that our bureaucratic civil servants are not justified in the philosophical application of the "science" they practice.

- MacIntyre describes the incompatibility (and yet incoherent coexistence in the Enlightenment) of empiricism and natural science (81)

- These changes in the 17th & 18th centuries changed the meaning of "fact" from an Aristotelean to a mechanist view (84)

- MacIntyre argues that the "scientism" of social behavior upon which our bureaucratic-expert-run Governments are based is flawed (86-88)

Ch 8 - The Character of Generalizations in Social Science and their Lack of Predictive Power

Summary: MacIntyre refutes the authority of bureaucratic managers by showing how the systematic unpredictability of social life (c.f. Taleb) makes the authoritative claims of modern social science—and by extension the downstream managers/economists who use them—fall apart.

- justification of managerial expertise requires social science providing law-like generalizations with strong predictive power, but these have failed to materialize (88)

- no one—including philosophers of social science—has called out social scientists for not delivering predictive laws because doing so would imperil the grounds for employing them and managerial expertise as a whole (89)

- this is hiding the true achievements of social science (90)

- MacIntyre gives four distinguished theses of social science, which (90-91):

- have recognized counter-examples

- lack universal quantifiers and scope modifiers

- do not entail any well-defined set of counterfactual conditionals

- "But let us suppose once again that the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, brilliant and creative as they were, were in fact centuries not as we and they take them to be of Enlightenment, but of a peculiar kind of darkness in which men so dazzled themselves that they could no longer see and ask whether the social sciences might not have an alternative ancestry." (92)

- Machiavelli differs from the Enlightenment tradition in a way MacIntyre approves of (93)

- Fortuna: given the best generalizations we can still be defeated by an "unpredicted and unpredictable counter-example" (Taleb's Black Swan)

- MacIntyre presents four sources of systematic unpredictability in human affairs (93+):

- first, a radical new invention cannot be predicted, because predicting it would amount to inventing it, c.f. Karl Popper (also cited by Taleb); this points to the unpredictability of the future of science (93-94)

- second, the unpredictability of the decisions of individual agents generates uncertainty in the social world...after citing Thomas, he says that "it is precisely insofar as we differ from God that unpredictability invades our lives"; MacIntyre then suggests that those who "seek to eliminate unpredictability from the social world or to deny it" are effectively claiming to be God (which in fact the "Humanitarians" do claim in Robert Hugh Benson's Lord of the World) (95-97)

- third, the failings of a game theory view of social life due to 1) infinite reflexivity (thinking an infinite number of moves ahead), 2) imperfect knowledge, and 3) multiple games or layers of games (97-99)

- fourth, pure contingency (tiny changes can have huge impacts) (99-100)

- Then MacIntyre presents four predictable elements of human life (102+):

- the schedule of a "normal day"

- statistical regularities (more colds in winter)

- knowledge of the causal regularities of nature

- knowledge of the causal regularities of social life

- MacIntyre suggests the systematic study of error in social scientific predictions as a first step in better understanding them (105, cf. Forecasting)

- "Organizational success and organizational predictability exclude one another", so certain kinds of Totalitarianism are impossible (106)

- all of this to reaffirm that the concept of managerial effectiveness is a moral fiction..."No one is or could be in charge." (107)

Ch 9 - Nietzsche or Aristotle

Summary: If you agree with MacIntyre about the failure of the Enlightenment project, you must then choose between the moral philosophy of Nietzsche or the classical tradition as embodied in Aristotle.

- If MacIntyre's argument thus far is correct, he says Nietzsche's moral philosophy is one of the two "genuine theoretical alternatives" (110)

- Discussion of Polynesian taboo as arbitrary and easily abolished (112+), as an example of how Nietzsche understood how appeals to objectivity were actually expressions of subjective will (113)

- "Nietzsche is the moral philosopher of the present age" (along with Weber), and Goffman provides the corresponding sociology (114-115)

- Nietzsche vs Aristotle is set up like this (117-118):

- First, the Enlightenment rejected Aristotle

- The Enlightenment failed

- Then along came Nietzsche who criticized all previous morality due to this failure

- ...but to agree with Nietzsche you have to agree with the initial rejection of Aristotle; If Aristotle (or something like him) can be sustained then Nietzsche is pointless

- so...can Aristotle be vindicated?

- "There is no third alternative" between Nietzsche and Aristotle

- We need to first understand the virtues before we can understand the modern conception of rules, a task to which MacIntyre devotes the rest of the book starting with the Iliad (119)

Ch 10 - The Virtues in Heroic Societies

Summary: MacIntyre describes the virtues in heroic societies as that what allows us to fulfill our societal roles with excellence.

- Stories are the chief means of moral education in classical societies (121)

- Action: "A man in a heroic society is what he does." (122)

- aretê (translated as virtue) is excellence of any kind (122)

- "Morality and social structure are in face one and the same in heroic society"...without social structure man would not know who he is (123)

- "...excellences or virtues are those qualities which enable an individual to do what his or her role requires; and a conception of the human condition as fragile and vulnerable to destiny and to death, such that to be virtuous is not to avoid vulnerability and death, but rather to accord them their due." (128-129)"

- history is important: "even heroic society is still inescapably a part of us all" (130)

Ch 11 - The Virtues at Athens

Summary: MacIntyre sees the common ground of ancient virtues as centered around the polis and agôn despite their varieties.

- heroic literature provided the moral scriptures of later societies; key moral characteristics arise from relating that literature to actual practice (131)

- Athens was the center of the questions of being a good citizen and being a good man (133)

- MacIntyre discusses the variety of views of virtues within Greece and Athens and cautions against assigning a single view, but all agree that virtues have their place within the social context of the polis (city-state) and agôn (games or contest) (134-138)

- interesting that humility, thrift, and conscientiousness don't appear in the Greek list of virtues (136)

- we are left with two frameworks for the virtues (142):

Ch 12 - Aristotle's Account of the Virtues

Summary: MacIntyre provides a tour of Aristotle's understanding of virtue, including the problematic portions that must be discarded—or partially replaced—if we are to maintain an Aristotelian view of morality.

- MacIntyre turns to give a view of Aristotelean virtues, not just as said by Aristotle but by the whole tradition from which he drew and upon which others have built (despite Aristotle's dislike for such a view of tradition) (146)

- The Nicomachean Ethics—"the most brilliant set of lecture notes ever written"—being the canonical text for Aristotle's account of the virtues (147)

- Every activity, enquiry, and practice aims at some good, or eudaimonia; the virtues allow us to achieve that (148)

- therefore, we can't characterize the good for man without making reference to the virtues (149)

- little reference to rules in the Ethics (150)

- Aristotle gives the notion of the mean between extremes to characterize virtues (154)

- Aristotle distinguishes between intellectual virtues acquired by teaching and virtues of character acquired through exercise; these can't be separated (154)

- Aristotle argues that one cannot possess any of the virtues of character without possessing all the others (155)

- Friendship for Aristotle as "that which embodies a shared recognition of and pursuit of a good" (155) and creating and sustaining the life of the city (156)

- Aristotle presupposes freedom to exercise virtue and achieve good, and in doing so writes off slaves/barbarians, as well as craft skill and manual labor; Aristotle had "little or no understanding of historicity" (159)

- to Aristotle the virtues cannot be defined in terms of the pleasant or useful (160)

- MacIntyre recognizes problems with some of Aristotle’s views, which he argues can be set aside while retaining his overall theory (162)

- specifically, for an Aristotelian account of virtue to stand we must replace his biology with an adequate account of telos (163)

Ch 13 - Medieval Aspects and Occasions

Summary: While recognizing the diversity of Medieval thought and disagreeing with the necessary unity of virtues in Aristotle and Aquinas, MacIntyre praises the Medieval advance in moral theory by virtue of linking biblical historical perspective with Aristotelian virtue.

- Note: the Aristotelian tradition we speak of is grounded in his Nicomachaen Ethics and Politics and not tied exclusively to them but in dialogue with them; balance between "Classical" (too broad) and "Aristotelian" (too narrow) (165)

- Luther on Aristotle: "That buffoon who has misled the church" (says more about the former than the latter) (165)

- Medieval culture was not monolithic but had a variety of conflicting strands to understand (166)

- Christian and pagan elements coexisted in cultures recently emerged from a Heroic society (166)

- The rediscovery of classical texts made the integration of pagan and Christian virtues a topic of philosophical and theological reflection (167)

- Discussion of Stoicism and virtue on 168-169, including the Stoic abandonment of a telos, which is followed in Europe with emphasis on law rather than virtue

- "Whenever the virtues begin to lose their central place, Stoic patterns of thought and action at once reappear. Stoicism remains one of the permanent moral possibilities withing the cultures of the West." (c.f. Ryan Holiday and the secular Stoic movement today?) (170)

- The virtue of charity is new from Christianity: first the telos of a final redemption, and second in the evil encountered along the way (175)

- Medieval view of virtue: allow men to survive evils on their historical journey (176)

- Idealized view of the world as orderly, as expressed in Dante and Aquinas (176-177)

- MacIntyre disagrees with both Aristotle and Aquinas about the necessity of the unity of the virtues (example of a Nazi), but suggests that there is an alternative (180)

Ch 14 - The Nature of the Virtues

Summary: MacIntyre sees disparate conceptions of virtue and offers a unified definition of virtue as that which allows us to realize the internal goods of practices. This does not capture all of what Aristotle meant by virtue so will need to be strengthened with a view of the telos of a unified human life.

- we have many different and incompatible lists of virtues...the Homeric, the Aristotelian, the New Testament...add to them Benjamin Franklin and Jane Austen (181)

- Homeric: virtue allows you to do what your role requires (184)

- Aristotelian: telos determines the virtues (184)

- New Testament: telos as in Aristotle, the good life for man (including supernatural good) is prior to the concept of a virtue (184)

- Jane Austen: addition of constancy and amiability (183), combines seemingly different accounts of virtues (185)

- Ben Franklin: addition of cleanliness and industry and reshaping of more traditional virtues (183), teleological but utilitarian (185)

- MacIntyre observes three different views of virtues (185):

- discharge social role (Homer)

- achieve telos (Aristotle, New Testament, Aquinas)

- utility (Franklin)

- MacIntyre then proposes that we can unify a core conception of virtue from these rival claims (186)

- MacIntyre suggests the concept of practice is the primary arena where virtues are exhibited and needed to give a core concept of virtue (187)

- practice defined as activity where internal goods are realized with excellence

- MacIntyre proposes a tentative definition of virtue (191):

- "A virtue is an acquired human quality the possession and exercise of which tends to enable us to achieve those goods which are internal to practices and the lack of which effectively prevents us from achieving ay such goods."

- Practices can equally flourish in societies with different backgrounds (193) and need institutions to cultivate them (194) and must be understood also in terms of virtue (195)

- MacIntyre's view of virtue grounded in practices is helpful but not complete and further needs to get at the unity of each human life and the telos of that life (203)

Ch 15 - The Virtues, the Unity of a Human life and the Concept of a Tradition

Summary: MacIntyre describes the understanding of social life required for the virtues, which finds its foundation in unity of narrative of a person's life which is at odds with the modern view of individualism.

- obstacles to unity of each human life as a whole (204)

- social: modernity partitions each life into segments

- philosophical: tendency to think atomistically about human action

- lack of unity makes it difficult to map Aristotelian virtues to the "parts" of a person's life (205)

- human behavior as constituted by both intentions and beliefs, leading to narrative history as the basic genre for discussing human actions (208)

- conversation is the form of human transactions in general (211)

- "The narratives which we live out have both an unpredictable and a partially teleological character" (216)

- "man is a story-telling animal" and stories are how we understand a society (216)

- we are the subject of the story that runs from our birth to our death, and we have to give an account of our actions (217-218)

- unity is provided by the two questions of "What is the good for me?" and "What is the good for man?" (218-219)

- our lives are a quest for the telos of the good life of man, and the virtues sustain us on this quest (219)

- "The good life for man is the life spent in seeking for the good life for man, and the virtues necessary for the seeking are those which will enable us to understand what more and what else the good life for man is." (219)

- our position, relationships, community, etc. form our "moral starting point", which is at odds with a modern view of individualism (220)

- "What is better or worse for someone depends upon the character of that intelligible narrative which provides their life with its unity" --> the lack of a unifying conception of life underlies modern denial of factual moral judgments (225)

Ch 16 - From the Virtues to Virtue and after Virtue

Summary: MacIntyre focuses on Hume's conception of virtue (singular) as illustrating many of the features of modern thought now that narrative unity and practice are removed from an understanding of the virtues.

- "One of the key moment in the creation of modernity occurs when production moves outside of the household" and put to the service of "impersonal capital" (227, c.f. Wes Baker)

- Key problem: "For if you withdraw those background concepts of the narrative unity of human life and of a practice with goods internal to it from those areas in which human life is for the most part lived out, what is there left for the virtues to become?" (228)

- having happened, now virtue can only be cast as relating to the expression or regulation of the passions of the individual (228)

- discussion of Hume's separation of natural and artificial virtues...eventually leading to virtue as a concept of preference (229-231)

- great phrase of Hume's: "the monkish virtues"...something to aspire to in the same way as "the dogma lives loudly within you" link (230)

- ...so, whose preferences reign? (231)

- three features of Hume's treatment of the virtues (which reoccur) (232+)

- virtues are divorced from their classical meanings

- a new emphasis on the relationship between virtues and rules

- shift from "virtues" as plural to "virtue" as singular

- the removal of telos leads to a reversion to Stoicism...Nature now becomes what God is for Christianity (233-234)

- discussion of Adam Smith's view of virtue (234-235) and "Republicanism" (French Revolution) view of virtue (237-238) and Jane Austen, who he identifies as the last great representative of traditional virtues (239+)

Ch 17 - Justice as a Virtue: Changing Conceptions

Summary: Justice is a fundamental virtue and MacIntyre shows how his prior argument applied to questions of justice and suggests deep problems in our political system as a result of the loss of a common conception of justice.

- If common agreement on justice is needed for political community like Aristotle says, then this lack threatens our own society (244)

- MacIntyre gives a hypothetical (but realistic) example of two different views of justice, and then gives their philosophical proponents (245-246):

- Rawls and the framework of the "veil of ignorance"

- Nozick claims that property ownership is just if it was acquired justly

- MacIntyre doesn't dispute either of their arguments, but shows how we have too many disparate moral concepts that we cannot settle rationally (252)

- "Modern politics cannot be a matter of genuine moral consensus. And it is not. Modern politics is civil war carried on by other means." (253)

- Resulting ambiguity of patriotism: "In any society where government does not express or represent the moral community of the citizens, but is instead a set of institutional arrangements for imposing a bureaucratized unity on a society which lacks genuine moral consensus, the nature of political obligation becomes systematically unclear." (254)

- "Modern systematic politics...simply has to be rejected from a standpoint that owes genuine allegiance to the tradition of the virtues; for modern politics itself expresses in is institutional forms a systematic rejection of that tradition." (255)

Ch 18 - After Virtue: Nietzsche or Aristotle, Trotsky and St. Benedict

Summary: MacIntyre concludes by saying that it's actually not "Nietzsche vs Aristotle", but rather "liberal individualism (or something like it)" vs "Aristotle (or something like it)". We need to form local communities to sustain morality through the coming new dark ages.

- MacIntyre again sets up Aristotle vs Nietzsche and asserts that Nietzsche does not win: particularly in the isolation of his view of greatness, which stands vastly apart from the community and practices and common good of Aristotelian virtues (257-258)

- the Nietzschean "great man" is a pseudo-concept representing individualism's final attempt to escape from its own consequences, and Nietzsche does not overcome modernity but is simply one more example of it (259)

- so, it's not "Nietzsche vs Aristotle", but rather "liberal individualism (or something like it)" vs "Aristotle (or something like it)" (259)

- "we still, in spite of the efforts of three centuries of moral philosophy and one of sociology, lack any coherent rationally defensible statement of a liberal individualist point of view"

- "the Aristotelian tradition can be restated in a way that restores intelligibility and rationality to our moral and social attitudes and commitments"

- MacIntyre anticipates a rebuttal as saying it is "liberal individualism" vs "Marxism" and proceeds to disagree; instead he sees "no tolerable alternative set of political and economic structures which could be brought into place to replace the structures of advanced capitalism" (261-262)

- MacIntyre's closing paragraph (263)

It is always dangerous to draw too precise parallels between one historical period and anther; and among the most misleading of such parallels are those which have been drawn between our own age in Europe and North America and the epoch in which the Roman empire declined into the Dark Ages. Nonetheless certain parallels there are. A crucial turning point in that earlier history occurred when men and women of good will turned aside from the task of shoring up the Roman imperium and ceased to identify the continuation of civility and moral community with the maintenance of the imperium. What they set themselves to achieve instead—often not recognizing fully what they were doing—was the construction of new forms of community within which the moral life could be sustained so that both morality and civility might survive the coming ages of barbarism and darkness. If my account of our moral condition is correct, we ought also to conclude that for some time now we too have reached that turning point. What matters at this stage is the construction of local forms of community within which civility and the intellectual and moral life can be sustained through the new dark ages which are already upon us. And if the tradition of the virtues was able to survive the horrors of the last dark ages, we are not entirely without grounds for hope. This time however the barbarians are not waiting beyond the frontiers; they have already been governing us for quite some time. And it is our lack of consciousness of this that constitutes part of our predicament. We are waiting not for a Godot, but for another—doubtless very different—St. Benedict.

Ch 19 - Postscript to the Second Edition

Summary: Consider After Virtue a work still in progress, with some brief clarifications on three points.

- his goal with After Virtue was to sketch the overall thesis of the place of virtues in human life and show how it was incompatible with conventional academic disciplinary boundaries (264)

- three areas to clarify:

- relationship of philosophy to history

- the virtues relativism

- relationship of moral philosophy to theology (see Nicomachean Ethics, Thomism and Aristotelianism by Harry V. Jaffa)

Prologue to the Third Edition (2007)

- subsequent works:

- "When I wrote After Virtue, I was already an Aristotelian, but not yet a

Thomist...I became a Thomist after writing After Virtue in part because I became convinced that Aquinas was in some respects a better Aris-

totelian than Aristotle" (x)- "So I discovered that I had, without realizing it, presupposed the truth of something very close to the account of the concept of good that Aquinas gives in question 5 in the first part of the *Summa Theologiae." (xi)

- Criticisms of After Virtue

- Nostalgia and idealizing the past (careless misreading) (xi)

- Relativism (xii), resolved on xiv: "Yet what matters most is that such issues can on occasion be decided, and this in a way that makes it evident that the claims of such rival traditions from the outset presuppose the falsity of relativism."

- Communist/"Communitarian" (xiv)

- "my understanding of the nature and complexity of traditions I owe most of all to J. H. Newman." (xii)

- xii+: situatedness is important but not relativistic, resolves on xi

- xiii: to respond to rival arguments/traditions you first need to fully understand the position of those arguments/traditions and their self-imposed limits, and ask if an external tradition can overcome them

- xvi: one tradition could "defeat" another with better truth claims, but the second could not know it was defeated

- xv: "what liberalism promotes is a kind of institutional order that is inimical to the construction and sustaining of the types of communal relationship required for the best kind of human life."

- xv: "When recurrently the tradition of the virtues is regenerated, it is always in everyday life, it is always through the engagement by plain persons in a variety of practices, including those of making and sustaining families and households, schools, clinics, and local forms of political community. And that regeneration enables such plain persons to put to the question the dominant modes of moral and social discourse and the institutions that find their expression in those modes."

- "After Virtue was written in part out of a recognition of those moral inadequacies of Marxism which its twentieth-century history had disclosed, I was and remain deeply indebted to Marx’s critique of the economic, social, and cultural order of capitalism and to the development of that critique by later Marxists." (xvi)

- >In the last sentence of After Virtue I spoke of us as waiting for another St. Benedict. Benedict’s greatness lay in making possible a quite new kind of institution, that of the monastery of prayer, learning, and labor, in which and around which communities could not only survive, but flourish in a period of social and cultural darkness. The effects of Benedict’s founding insights and of their institutional embodiment by those who learned from them were from the standpoint of his own age quite unpredictable. And it was my intention to suggest, when I wrote that last sentence in 1980, that ours too is a time of waiting for new and unpredictable possibilities of renewal. It is also a time for resisting as prudently and courageously and justly and temperately as possible the dominant social, economic, and political order of advanced modernity. So it was twenty-six years ago, so it is still. (xvi)

Resources

- See the section on After Virtue in The Theology of Robert Barron, 161-169

New Words

- solipsism: The theory that the self is the only thing that can be known and verified (258)

Created: 2020-11-18

Updated: 2025-09-07-Sun